The Golem is arguably the most recognizable and enduring symbol in Ashkenazi Jewish folklore. The symbol originates in the Tanakh, in Psalm 139:16, where the term refers to “unformed limbs.” The figure of the Golem reemerged in medieval Europe as a symbolic response to the violence and persecution faced by Jewish communities throughout Christendom.

The most well-known version of the legend centers on Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the sixteenth-century leader of Prague’s Jewish community, better known as the Maharal. Responding to rampant anti-Jewish violence faced by his community, the Maharal fashioned a clay Golem to protect the Jews of Prague. Through mystical Jewish rituals and Hebrew incantations, he brought the creature to life, inscribing the word אמת (Emet), meaning “truth,” upon its forehead. Although the Golem succeeded in protecting the community, it also wrought destruction. Ultimately, the Maharal was forced to terminate his creation by rubbing out the א above the creature’s eyes, leaving the word מת (Met), meaning “death.”

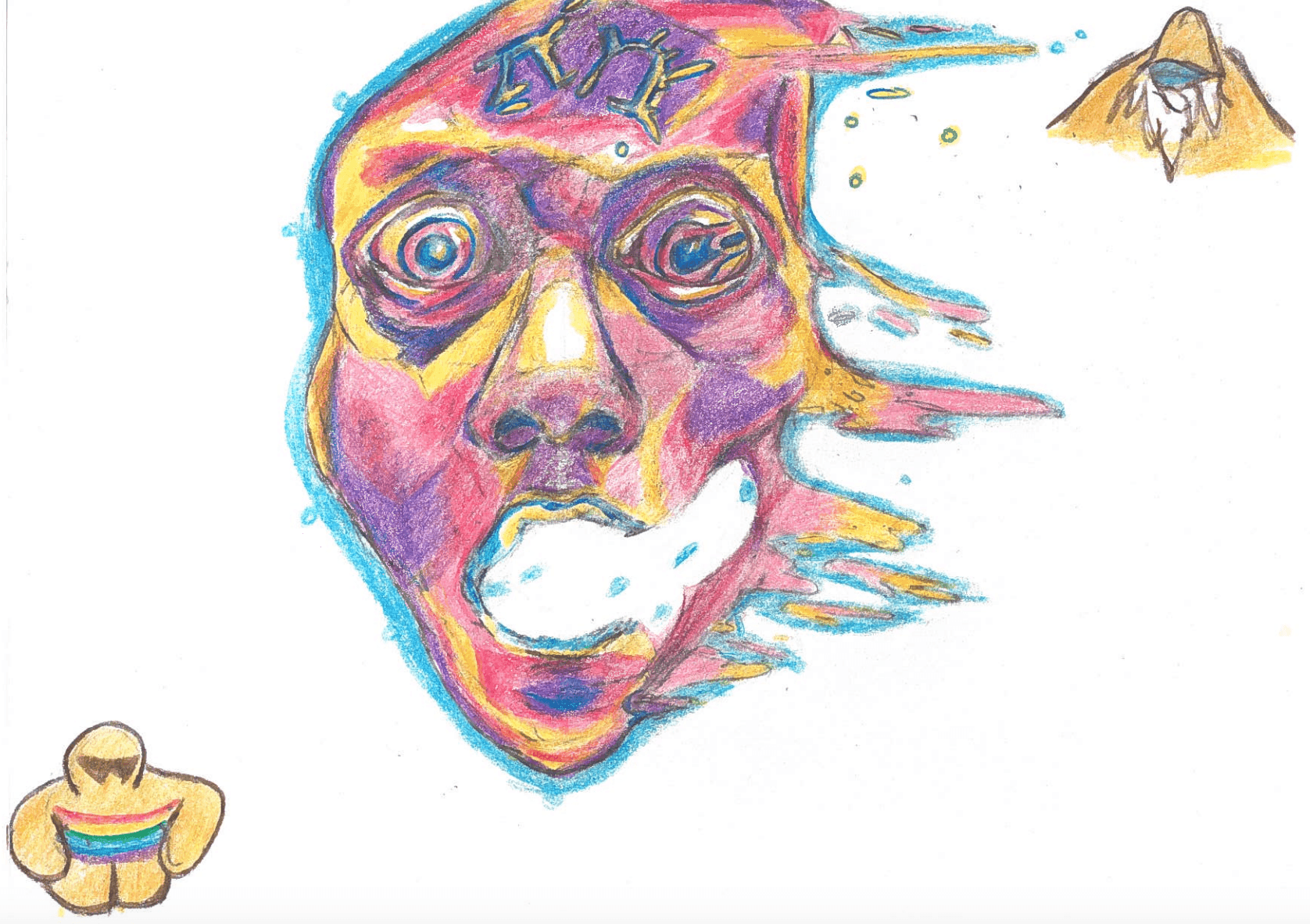

The Golem, representing themes of Jewish mysticism, religious creativity, and the moral complexity of resistance to antisemitism has a renewed significance within progressive Jewish communities across the diaspora. To understand this resonance, I interviewed two Jewish artists, Shoshana and Cliel, both of whom frequently employ the Golem in their artwork. Shoshana studies Visual and Critical studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Cliel recently began a PhD in Queer Bible Interpretation at the University of Toronto. Shoshana and Cliel helped shed light on my central question: Why do so many progressive Jews in the diaspora feel such a deep connection to the Golem, and what does this symbol represent for them?

For Shoshana, who has been deeply engaged in Jewish religiosity for many years, there exists a severe lack of spirituality in most mainstream diasporic spaces today. The Golem narrative, by contrast, offers an example of intensely spiritual, even mystical, diasporic Judaism. The Golem thus bridges contemporary Jews in the diaspora to spirituality and religious creativity.

Both Shoshana and Cliel also offered queer readings of the Golem story. Shoshana connects the symbol of the Golem to the transgender body, drawing a parallel to the biblical creation story of Adam and Eve, based on the “idea of something being created and having life breathed into it.” While the Adam and Eve narrative is often interpreted through a rigid gender binary, the Golem offers a more fluid, expansive conception of creation. For many queer and trans Jews, this fluidity makes the Golem a deeply affirming symbol.

Similarly, Cliel reflected on the Golem’s portrayal as a “monster,” a label that she claims derives from its “too-muchness.” Queer people, she explained, are often expected to conform to heteronormative behavioural expectations; when they do not, they are likewise labeled as “too much.” In this sense, the Golem becomes a powerful emblem of queer resilience – a being not made like everyone else, but still endowed with power, purpose, and dignity.

Finally, both Shoshana and Cliel interpret the Golem as a framework for thinking about how Jews today can responsibly respond to antisemitism. Shoshana noted the duality of the Golem: It saves the Jewish people, yet also causes massive amounts of destruction. This moral complexity mirrors the nuanced question of Jewish power today. We must recognize and confront the reality that Jews today hold differing degrees of power in the global struggle against antisemitism. With that power comes great responsibility: to safeguard ourselves and our communities without reproducing the harm we have long sought to resist.

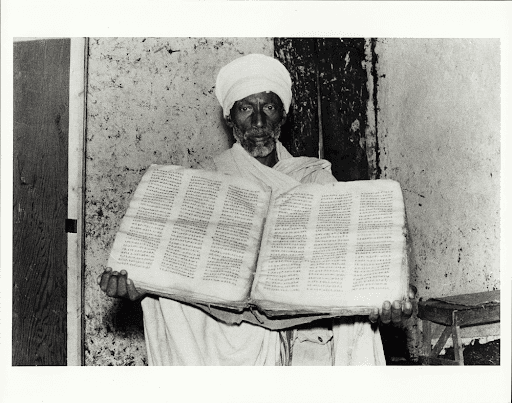

For Cliel, who in recent years has begun crocheting plush Golomim, the Golem embodies protection. During moments of rising antisemitism and emotional distress, creating crochet Golemim offered them something tangible in which they could find comfort. Over time, Cliel began gifting her handmade Golemim to Jewish friends. To me, this practice beautifully illustrates the most essential response to antisemitism: community. As Jews in the diaspora, we must continue to cultivate caring and committed communities – spaces of solidarity, creativity, and love to sustain us through adversity.

Powered by Froala Editor