UNITY UNITY UNITY – like a hollowed hymn, the word echoes faintly. The choir is tired, and so are we. Over the past year and half, ‘Jewish Unity’ has become somewhat of a buzzword across the mainstream Jewish world. But what does the word actually mean? How must we, as Jews today, conceive of this ever-so delicate ideal?

This week’s parasha, Bo, tells of the final three plagues that Hashem inflicts upon Egypt and the miraculous liberation of Bnei Yisrael after 430 years of subjugation in Eretz Mitzrayim. At the beginning of the parasha, Moshe and Aharon approach Pharoah with their classic ‘let my people go’ spiel. Pharaoh rejects their demand, but he does offer them the opportunity to take a “delegation” of Israelites out of Egypt so that they may worship Hashem. Moshe, with good reason, is unsatisfied with Pharoah’s offer, insisting that “we will all go.” From this, our understanding of the importance of Jewish unity is first established. If Moshe was willing to sacrifice the liberty of some Israelites for the sake of Bnei Yisrael’s unity, so too must we work towards achieving the unity of the Jewish people today.

However, this unity is not unqualified. After Hashem plagues Egypt with devastating swarms of locusts and an impenetrable darkness, Pharoah improves his offer to Moshe. He implores him: “Go, worship Hashem! Only your flocks and your herds shall be left behind; even your dependents may go with you.” Although Pharaoh seemingly agrees to free the entirety of Bnei Yisrael from their bondage, Moshe is still unsatisfied. He demands that Pharaoh also provide Bnei Yisrael with animals to be sacrificed to God during their journey through the Egyptian wilderness. Through this bold statement of faith, Moshe affirms that Jewish unity means nothing if we must sacrifice our tradition in order to achieve it.

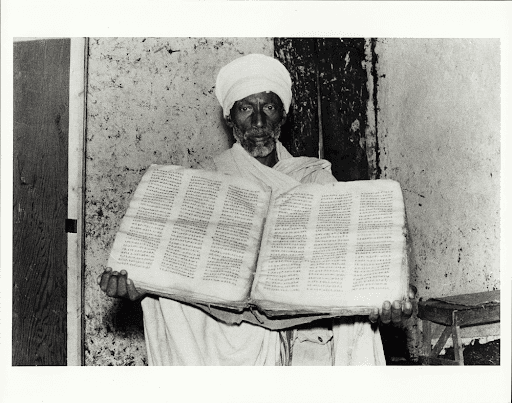

Jewish tradition has long centered on a deep-seated faith in God and a commitment to the mitzvot delineated in the Torah. But today, in our emancipated Jewish world, this no longer holds true. Agnostic Judaism is everywhere; its members are deeply committed to Jewish practice and intimately connected to their Jewish identities, albeit removed somewhat from the traditional conception of God and Halakha. I, myself, am one such Jew – as are the vast majority of Nu magazine’s staff and many of our readers.

According to the Torah, however, Jews who do not adhere to its laws have no place in Am Yisrael. One such pasuk in parashat Bo declares that “whoever eats what is leavened” (chametz) on Pesach, “shall be cut off from the community of Israel.” Indeed, if we accept strict observance of the laws of a divinely inspired Torah to be our sole conception of Jewish tradition, much of the thriving community that makes up this publication would be excluded from the unity of the Jewish people.

Rav Jacob Ettlinger (the Binyan Tziyon), hailed as one of the most illustrious Rabbinical figures of the 19th century, famously recognized that in an emancipated Jewish context, those who “desecrate” Shabbat rarely do so as a means of revolting against their faith or their membership as a part of the Jewish people – as was assumed in the stagnant and insular Jewish communities of the pre-emancipated world. Rather, as a result of our emancipation, millions of modern Jews have been exposed to a world teeming with rich alternative ideologies that have influenced our understanding of Jewish theology and practice of Jewish ritual. Although the Binyan Tziyon by no means condones these non-traditional conceptions of Judaism, he concludes that even the Jew who openly violates Shabbat must not be ostracized from their community because they still, more than likely, care about Judaism – albeit a form of Judaism not entirely based in strict Torah law.

It seems, then, that we, as modern Jews, are tasked with redefining this idea of Jewish tradition for ourselves. As such, we must pursue learning, experience, and relationships of all sorts in order to discover for ourselves which aspects of Jewish tradition are most important to us. It is only then that we can work to unite. Around what, you ask? Our collective care for this beautifully multiplicitous tradition – and, in turn, for each other.

Powered by Froala Editor