Conceptions of Jewish culture are usually viewed as “ashki-centric”—lox, matzah ball soup, and oy veys mark the mainstream depictions of Jews around the world. In reality, however, our culture is shaped by a vast array of traditions from across the globe. In Montreal, 25% of the Jewish population identifies as Sephardi or Mizrahi, a testament to Judaism's diverse heritage and practices. We are also fortunate to have a small but vibrant Ethiopian Jewish community, the Beta Israel, who further enrich the exchange of traditions and practices within our city’s Jewish community. The Beta Israel deepen the rich diversity present in Montreal and Jewish communities across the world, preserving their unique traditions while contributing to the religion’s vibrant life and culture.

A Beta Israel community has existed in Montreal since 1979, but its history spans generations. Some members consider themselves the descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, while other tales trace Beta Israel’s origins back to the lost tribe of Dan or even to Jews fleeing the Ancient Kingdom of Israel after the destruction of Solomon’s temple in 578 B.C.E. No matter how they arrived in Ethiopia, they managed to keep their identities and religion, fighting to maintain their culture and practices.

In the 1960s and 70s, as the lives of Beta Israel became increasingly imperiled due to rising political tensions and religious persecution, Jews around the world sought to extricate them from Ethiopia. The journey to flee was fraught with danger, requiring a trek through the Sudanese desert that could take anywhere from weeks to months. In the late 1970s, Baruch Tegegne, one of the first Ethiopian Jews to arrive in Israel, took action. Through diplomatic efforts and fundraising, he personally ensured some of the evacuations of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan.

In 1979, Tegegne and his wife moved to Montreal and brought with them the desire to continue helping the Beta Israel. Once again, he spearheaded efforts to bring Ethiopian Jews to safety. Galvanized by Tegegne, the Montreal Jewish community sponsored the immigration of Ethiopian families in the 70s and 80s before Operation Moses and the mass migration of Ethiopian Jews to Israel. Now, Montreal has one of the largest Ethiopian Jewish communities outside of Israel. The members of the community never resided in Israel, and as a result, their traditions remain uninfluenced by Israeli culture.

At its peak, the Beta Israel community contained about 400 members. Those who emigrated were welcomed into a Jewish community rich with diversity. “Moroccan Jews were some of the first to help the Ethiopian Jews,” said Yaffa Tegegne, the late Baruch Tegegne’s daughter, in an interview with Nu. She accredits this willingness to assist the immigrants to their shared African heritage. In Montreal, the children of Beta Israel grew up going to the same schools as Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews, praying in the same synagogues, and interacting in shared communal spaces while learning about their community’s distinctive traditions.

Though Montreal’s Beta Israel only contains around 25 families today, they continue to uphold their practices. In recent years, members have begun to educate the broader Jewish community about their customs, traveling to Hillels, Jewish Day Schools, and other community centres. “You need to show who you are, and be proud of yourself,” said Yaffa Tegegne. “I live with a legacy, and I try my best to uphold it and support my community and use my voice however I can, whether it be through outreach and education or Jewish diversity training.”

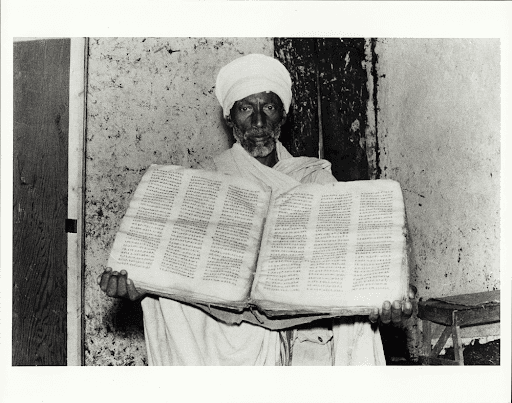

Part of Tegegne’s mission is educating on Ethiopian Jewry’s unique practices, which developed independently due to their historical isolation from the wider Jewish population. They did not have access to the oral Torah, and as a result, particular halachic customs were adopted differently in their communities. For example, the prohibition against “cooking a calf in its mother’s milk” was not interpreted as restricting the combination of milk and meat, but rather the eating of nursing animals. The rules of observing the Sabbath were interpreted differently as well—the Beta Israel have no rule against touching money on Shabbat, and charitable donations have even become a central part of the Shabbat service.

Beta Israel also practices Sigd, a holiday occurring 50 days after Yom Kippur that marks the renewal of the covenant between God and the Jewish people. Traditionally, the Beta Israel climb a hilltop and, facing Jerusalem, pray in Ge’ez, their ancient liturgical language. Now, in Montreal, Beta Israel shares this tradition with the broader Jewish community every year.

Montreal’s Beta Israel community stands as a testament to the resilience and diversity of Jewish identity. As people like Tegegne continue to share their history, celebrations, and traditions, the customs of Beta Israel become cemented in Judaism’s culture—adding sanbat wat and dabo to our mix of bagels, kugel, and kvelling.

Powered by Froala Editor