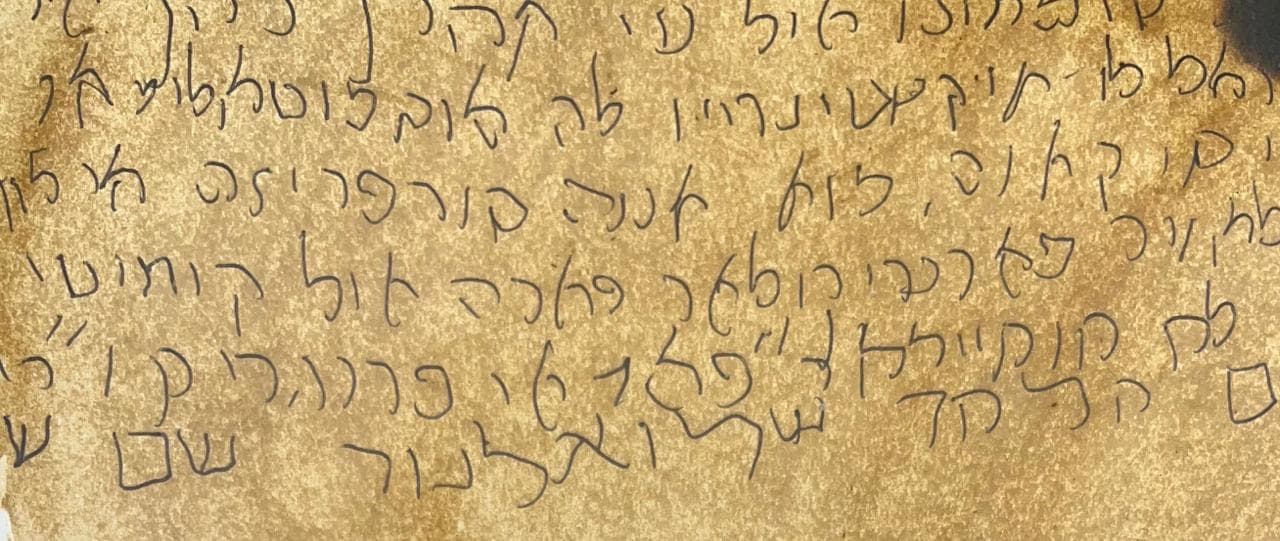

The Diaspora experience, characterized by exile, migration, and assimilation, often found Jews in a balancing act between integrating into diverse cultures and maintaining a connection to their identity. The fusion of Hebrew with countless other local languages embodies this experience, as language allowed Jews to remain both deeply grounded by tradition and reap the rewards of assimilation. Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, and other languages all illustrate the liminal space Jews have occupied between integration and apartness. Linguistic synthesis allowed Jews to play major roles in local economies and thrive in political and intellectual spaces, but also served as clear indicators of Jewish distinctiveness.

While fusion dialects enabled Jews to become some of the greatest philosophers, scholars, writers, and artists of the diaspora lands (think Spinoza, Maimonides, Sholem Aleichem, or Marc Chagall), these languages also carried a fundamental tension that has defined the Jewish experience for centuries: the pull of historical memory against the push toward modernity and assimilation. An early push toward assimilation, Jewish fusion dialects emerged out of a need to successfully function in new social contexts. The development of Judeo-Arabic allowed Jews to integrate into trade networks and become successful merchants, while Ladino played a key role in allowing Jews into the elite circles of the Ottoman Empire after the Spanish Inquisition. Yiddish was the vehicle that facilitated the political mobilization of Europe’s Jews, and Judeo-Persian allowed Jews to play key roles in Silk Road trade networks. Despite the comprehensive social integration illustrated in each of these cases, the unquestionable Jewishness of these fusion dialects also enabled Jews to maintain their cultural and religious identity, pulling them toward their historical roots.

The harmony between the Jewish and secular aspects of diaspora identity reflected in fusion dialects became more conflictual during moments of heightened antisemitism. The marginalization of Jewish communities, manifested in the foreignness of the languages they spoke, was often inescapable. “In general, they were seen as jargon,” said Sarah Bunin Benor, director of the Jewish Language Project and professor of contemporary Jewish studies and linguistics at Hebrew Union College, in an interview with Nu. “They were looked down upon as corrupted versions of the local language because Jews were looked down upon. When a group is stigmatized, their language is stigmatized.”

As the rising tide of nationalism swept across Europe and later the Middle East, the otherness of Jewish language began to reflect the pressing “Jewish Question” of the day: Could Jews could truly be a part of the nations they resided in? This dilemma was often answered in two ways. The first was the demand that Jews completely strip themselves of any unique cultural identifiers that would set them apart from the rest of the nation, of which language was vital. The second, yet more sinister, was the complete removal of Jews from these nations through expulsion or total extermination. After the violent persecution of the communities that spoke these Jewish languages resulted in their decline, the varied reactions to this repression further highlighted the push-pull tension between assimilation and connection to history. Due to trauma from persecution and the upward social mobility that came with assimilation, many Jews completely abandoned fusion dialects in favor of dominant local languages. Holocaust survivors, for example, often refused to teach their children Yiddish. On the other hand, some Jews promoted a complete divorce from diaspora societies through a return to the common thread connecting fusion dialects: Hebrew. In any case, many of these languages that once defined the Jewish diaspora experience began to fade away.

For Bunin Benor, though, there are ways to mitigate the sense of loss that comes with losing these languages. “Heritage words…words that are from your ancestral language that you continue to use even after your family stopped speaking it,” help maintain a “connection” to the language, she says. Heritage Words is the name of her podcast in which she interviews people with connections to these Jewish ancestral languages, highlighting the intricate mosaic of Jewish language.

Jewish fusion dialects are not a phenomenon of the past, however. New blends such as Jewish English spoken in North America can be understood as their own dialects, as a non-Jew probably wouldn’t understand: “I’m going to daven Mincha at shul before heading to the deli for some cholent.” Furthermore, integrations of diaspora languages into Hebrew after various immigration waves to Israel have produced their own quasi-dialects. It should be noted that fusion dialects like these, such as Jewish English, Judeo-Arabic, and dialects that have been spoken in Israel, differ from Yiddish and Ladino in an important way: While Yiddish and Ladino were maintained on their own for centuries and were their speaker’s primary means of communication, most other languages have existed within the structure of the host language and have not served as the only linguistic medium their speakers use. For example, Yiddish speakers in 18th century Europe spoke Yiddish at home, did business in Yiddish, and read Yiddish newspapers, while speakers of Jewish English only use it in specific situations.

The diversity of Jewish language reflects the heterogeneity of the Jewish people and is a testament to the resilience of Jewish identity. No matter where Jews went, language connected them to their past and their story. Although most Jewish fusion dialects aren’t widely spoken anymore, their legacy remains crucial to understanding the struggle between adaptation and preservation that defines Jewish life still today. The importance of the Jewish relationship to language is encapsulated in theologian and philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel’s quote, “words create worlds.” These languages haven’t been just means of communication. They remain vessels of identity, holding the essence of the Jewish experience.

Powered by Froala Editor