For professor, documentarian, and native Montrealer Garry Beitel, documentary filmmaking is a medium that blends creative activism with his Jewish heritage. In his class at McGill, Jews in Film, Beitel takes his students through different Jewish stories thoroughly and with care. While encouraging analysis of the on-screen narratives, Beitel’s class also prompts students to take introspection beyond the classroom.

Born in Outremont to Jewish refugees from Poland, Beitel studied Political Science and Sociology at McGill, enrolling in a number of film courses along the way. Attending university during the culturally and politically dynamic 1960s prompted him to find a point of entry into the world of advocacy and social justice. “My interest in film came about through politics,” he said in an interview with Nu Magazine. “I was torn between social work and filmmaking.” Ultimately, being a documentarian enabled Beitel to do both.

A key turning point in both his career and Jewish identity came in 1991 with the release of his film Bonjour! Shalom!, set in his very own Outremont. The film documented the “tension in Outremont between the Hasidic Jewish population, which was growing tremendously in numbers, and the French population.” As the conflict persisted, Beitel felt increasingly obligated to tell this story of local tension and “to expand the vision of people who saw Jews only as Hasidim.”

Throughout the process of its creation, Bonjour! Shalom! became as much a reflection of Beitel’s own Jewish identity as it was a portrait of Outremont’s communities. “It changed my relationship with my own past, with my Jewish culture. I started feeling less embarrassed and more comfortable. More than that, I started to realize that I could be Jewish without being a religious Jew,” he said.

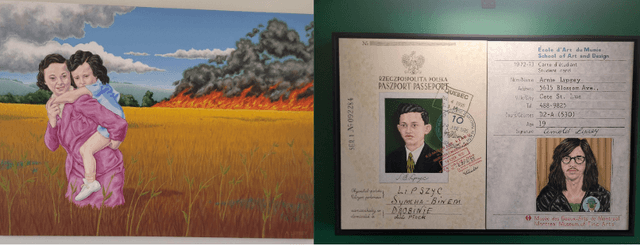

While a number of Beitel’s other films, like My Dear Clara and The Socalled Movie, engage directly with Jewish subject matter, many others, like In Pursuit of Peace and Asylum do not. Seemingly non-Jewish in their content, they tell the stories of Mexican farm workers coming to Quebec, newly-arrived Haitian taxi drivers, and asylum-seeking refugees. Yet, these films, too, possess a creative essence rooted in Jewish culture and a certain “Jewish sensitivity”?

Being a member of a minority group that’s often misrepresented, Beitel’s “sensitivity” to nuanced realities and focus on underappreciated stories come from a Jewish place. “These aren’t particularly Jewish subjects, yet they pull on me as a Jew who has a consciousness of being a member of a minority group that has been discriminated against,” he explained. His motivation was to “have an impact on people” by “making them aware of little-known realities.”

For Beitel, filmmaking became “an opportunity to make an impact on the world as a part of Judaism.” It is this awareness, this Jewish sensitivity, that allows his films to speak to the Jewish experience while illuminating a universal story of resilience amidst persecution.

To wrap up our interview, I asked one final, somewhat indulgent, question: “If you could have lunch with one Jewish cultural figure who would it be?”

While I internally toggled between Sacha Baron Cohen and Jesus, Beitel chose Leonard Cohen, the legendary musician depicted in Montreal murals and arguably more internationally famous than maple syrup. His well-known songs, such as Suzanne and So Long Marianne, act as modern epics, regaling tales of love and loss. Within these melancholic ballads, his songwriting has the same Jewish sensitivity that defines Beitel’s films and embodies a part of Jewish culture.

As Beitel put it, “It's his draw to both love and darkness” that pulls him and so many others to Cohen’s signature sound. In his embrace of the struggles and bittersweetness of life, Cohen’s music echoes Beitel’s Jewish sensitivity. Regardless of artist or medium, perhaps Jewish sensitivity is a common thread that gives Jewish culture as a whole its timeless and existentially enticing “je ne sais quoi.”

Powered by Froala Editor

-3ZGJhiZHGXhQOKyTd244n742gtmbYe.png&w=1920&q=75)