Mireille Silcoff began her career in journalism mostly by accident. She started a clothing brand targeted toward young adults for the Montreal clubbing scene and wrote leaflets to promote her brand. Soon, the leaflets became even more successful than the clothing itself. Then, as a music columnist at the Montreal Mirror, she began her career as a journalist. Since then, she was a writer and senior editor at the National Post, wrote four books including the best-selling Chez L'arabe, and now writes for the New York Times.

“Meandering is a bit of a lost art; meandering, tossing around ideas that are useless in your head,” according to Silcoff. Beyond her inspiration as an intellectual, Silcoff has used her curiosity to revitalize Jewish culture. In an interview with Nu Magazine, Mereille shared her insight about Jewish journalism, culture, and thought.

How does your Judaism affect your writing?

Jewishness affects every single thing in my life. And of course, it affects my writing; I am, in my voice, an intensely Jewish writer. I am, in my thinking, an intensely Jewish thinker. I can get very Talmudic about a shoelace. Jewishness affects everything I do. At the very, very root of my thinking, Jewishness is there, and always has been.

How has your journey with Judaism intersected with your career?

I went through every phase of being a Jew as a young person. I went to Bialik High School, which was a weird fit for me, because it felt a little bit cloistered. And then I rebelled hard against Jewishness after high school, and I changed my name from Silcoff to Silcott because I thought it sounded less Jewish. Then, suddenly, I became a “professional Jew,” talking in synagogues and speaking to various federations across America about resuscitating Judaism for young people. And I went back to Silcoff. There are many chapters to my Jewish identity. But at the root of my thinking, even when I was Silcott, was always Jewishness.

What was the magazine Guilt and Pleasure Quarterly? How did it impact Jewish culture?

Guilt and Pleasure Quarterly was a Jewish cultural magazine that came out of New York. We had this gilded board of writers and amazing people contributing to it. We were trying to resuscitate a kind of intellectual Judaism that was not really so much in the conversation back then. In the early 2000s, you encountered a lot of, “I’m Jewish, but….” There was a lot of shame. And I wanted to create a magazine that’s like, “Yeah, I’m Jewish. Like, boldly, I’m Jewish.”

We were really trying to resuscitate a culture that is young Jews. Growing up in the ’80s, we dreamt that we would see these movies and dream of having a Jewish world that felt something like that. But it didn’t feel like that in Montreal, or it didn’t feel like that where I was living at the time, which was Toronto and New York. And so we made it, and it was great.

The original idea for the magazine was [to share] fascinating conversations with the most fascinating people we can find. Every issue had a topic, so as a project of some kind of dissemination of Jewish connectivity, Guilt and Pleasure Quarterly was unbelievably successful in the short amount of time that it existed.

What inspired you to begin your salons? What are the salons that you run?

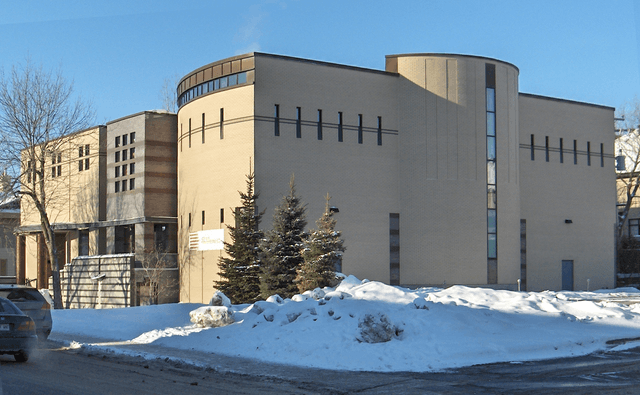

Well, I started them in Toronto in the early 2000s. I wanted to be a Jew, which was to sit around with other Jewish people, speaking deeply about all kinds of important topics and connect[ing] with people under an umbrella of ideas, rather than ideology or rather than religion. It would be around 14 people, but I would try to get really amazing people, mainly journalists and media people. But it did so well that eventually I needed to move it out of my apartment and moved it into the basement of the Drake hotel in Toronto, which had just been built. I had them every month or every couple of months, and it was very much like a live magazine. I do something very similar now in the Museum of Jewish Montreal.

What is your advice for Jewish writers now?

It’s an increasingly hard landscape in which to identify as Jewish. This is a new world. Culture still needs to live and still needs to be documented. This is one of the important things to do right now. It is maintenance and keeping continuity in Jewish culture; Judaism has always been a very cultural concern.

Responses were edited for clarity

Powered by Froala Editor