I arrived at Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom with a faintly defensive posture, not knowing what to expect from the upcoming event. The title, Golems and Guardians: Jewish Folklore, Identity, and the Superhero Narrative, suggested either revelation or politely endured enlightenment. Still, I went. Partly out of curiosity, partly because free talks are a student’s natural habitat, but mostly because I have loved superheroes since I was a child. I expected a lecture; what I got instead was a family story including clay giants, caped men, immigrant anxieties, and the enduring Jewish obsession with arguing with God, history, and ourselves. Rabbi Luks-Morgan began where any respectable Jewish tale should begin: with the golem. Not the pop culture Frankenstein cousin, but the folkloric creature molded from earth and animated through sacred words. The golem exists to protect, summoned in moments of danger, follows commands imperfectly, and grows too powerful for its own good.

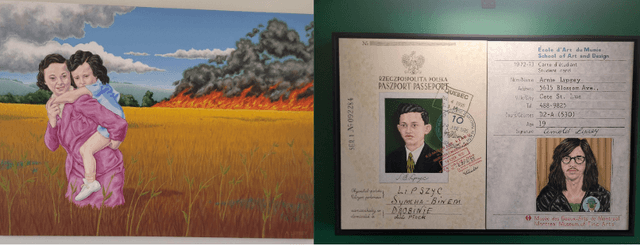

Long before spandex and cinematic universes, Jewish storytelling was full of reluctant protectors, moral complication, and power laced with anxiety. Samson, whose strength is divine and disastrously human. Moses, raised between two worlds, marked from birth. Elijah, appearing when things have gone off the rails. Rabbi Luks-Morgan’s talk traced how this sensibility translated into early comic books, a medium largely built by the children of American Jewish immigrants. Many of their parents worked long hours in the garment factories, surrounded by fabric.. The image of parents coming home with scraps of cloth stuck with me: children growing up in cramped apartments surrounded by texture, color, and possibility. Those scraps became costumes. Imagination rarely asks permission. Extra fabric becomes a cape and a simple outfit becomes symbolic armor. The superhero silhouette, all flowing lines and dramatic movement, owes something to the cutting tables of New York sweatshops; it is hard not to love that. They took these dreams, and created heroes who hid their true identities and passed as ordinary while living double lives.

Superman, famously, fits squarely into this tradition. His story mirrors that of Moses with almost embarrassing precision. A baby placed in a vessel, sent away from a doomed homeland. Instead of a basket in the Nile, a spaceship from Krypton. Instead of Pharaoh’s daughter, an all American farm couple in Kansas. A child between worlds who grows into a moral force. Then there is The Thing, Ben Grimm. Rough voice, rock body, with a soft Jewish heart. Canonically Jewish and stubbornly so, he drops Yiddish, celebrates Hanukkah, mourns his losses, and cracks jokes to survive a body that is monstrous instead of beautiful. There is something deeply Jewish in that arc, the insistence that dignity is not dependent on appearance.

Captain America belongs in this lineage as well. On the surface, Steve Rogers looks like pure American myth. Brooklyn kid. Bad asthma. Worse odds. Before he becomes a symbol, Steve is small, fragile, and chronically underestimated. He wants to fight evil with the kind of aching sincerity usually reserved for prayers. In Jewish folklore, the golem is never created because someone desires domination. It is created because danger has become unbearable. Captain America is deliberately designed, constructed and brought into being because the world is breaking. He is, in this sense, less a miracle than a modern golem, shaped with intention for the singular purpose of standing between catastrophe and the people who would otherwise be crushed by it. Even the figure who creates him echoes tradition. Dr. Abraham Erskine, the scientist behind the serum, is a refugee from Nazi Germany. A Jewish man who flees genocide and arrives in America carrying both scientific knowledge and moral urgency. In older stories, it is a rabbi who fashions the golem from clay. A scholar who understands letters, formulas, and consequences. Erskine is not merely a technician. He is a guardian of ethics.

In the end, whether formed from clay or ink, stitched from silk or summoned by sacred words, these heroes carry the same inheritance. They are built not to conquer, but to guard. Not to rule, but to endure.

Powered by Froala Editor