Asa Fradkin is a dear family friend and a hazzan (cantor) at Congregation Beth-El in Bethesda, Maryland. His clerical position entails responsibility for all things music-related at his Conservative synagogue. Accordingly, his seminary thesis was concerned with music’s role in Judaism—how it can make spirituality more accessible and deepen connection to Judaism. Where our families met happens to be a catalytic context that inspired his work.

In the early ‘80s, our two Jewish families converged at a Hindu yoga community (ashram) in rural Pennsylvania. My grandfather, a former emergency room doctor, was experiencing serious health issues. He opted for the holistic care provided at the ashram—a dramatic shift in diet and lifestyle. While raising my mother, he became friendly with the Fradkins and their toddler twins, Asa and Aryah. Their households meshed, and together, they immersed in spiritual enrichment and a deeper sense of meaning provided by the intentional community. This upbringing, in alignment with the phenomena of Hinjews and JUBUs (Jewish Buddhists), contributed to the curiosity underlying his thesis: Why do Jews seek spirituality outside of Judaism?

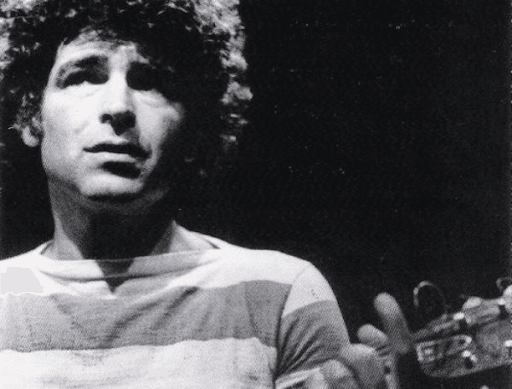

In an interview with Nu, Fradkin recounted a curious scene that opens his thesis: A throng of Upper West Side Jews funnelling into a service in New York City—but not a Jewish service. Rather, a Krishna Das concert where the traditional Hindu musical practice of kirtan is performed. For anyone intrigued, the devotional chanting-led service looks like this. Given the remarkable number of enthused Jews in attendance, Fradkin felt that “whatever they were getting from this, they weren’t getting from synagogue.” He believes while the comforting routine of synagogue strengthens Jewish heritage and tradition, Jews can easily drift from Judaism when services fail to provide satisfying spiritual fulfillment seemingly felt by Krishna Das’s audience.

Hindu traditions have their own complexity with historical roots as deep as Judaism. Yet with kirtan specifically, Fradkin noted that finding immediate spiritual connection with kirtan is almost inevitable: “Even though it’s in another foreign language, there’s just no barrier.” Contrasting this immediacy, Fradkin shared that spiritual connection in Judaism requires more effort.

This is in large part due to the insular nature of Judaism, which is, as Fradkin put it, “a religion of people in the know.” Observing Shabbos or keeping Kosher requires considerable knowledge of Jewish laws. Knowledge of Jewish history is required for understanding the plethora of traditions in each holiday—not to mention a baseline understanding of Hebrew and familiarity with the progression of weekly services.

While this intricacy provides Judaism with richness and beauty, it can also be tedious for Jews who do not follow their religion with complete devotion. Without a certain fluency in Judaism, “you’re out of the loop.” Music, Fradkin said, is the best way to break down such barriers and facilitate the connection congregants feel to their Judaism.

I attended a Shir Yachad service at Fradkin’s synagogue over winter break. Even as a cultural Jew raised outside of synagogue, I was immersed in music and the rhythm of familiar melodies. Despite not understanding Hebrew, I felt an unquestionable resonance with the service and other Jews in attendance.

Fradkin sees a broader trend of instrumental music being incorporated into non-Orthodox services. He credits the rising popularity to the services being “shorter and more engaging, rather than longer and more intellectual.” This raised the concern that Jewish tradition might erode in appealing to shorter attention spans—Fradkin is not worried. At his Conservative synagogue, it is now rare to have a Friday night service without instruments. However, he explained that “there’s almost a mechitzah people have put up between Friday night and Saturday morning services,” which remain unchanged, focused on prayer and Torah.

What matters most to Fradkin is ensuring that Judaism remains relevant in the lives of assimilated Jews. “One hundred years ago, nobody was saying ‘we’ve got to teach the kids why Judaism is relevant.’ It’s obviously relevant if you’re living in a community where everyone you know is Jewish.” Fradkin feels that affirming the relevance of Judaism is particularly important in suburban communities where other activities can often take priority.

He pointed out people are religious about many aspects of their lives—consistent meditation, yoga classes, and especially sports, are central to the weekends of countless Jews. Clearly there is capacity for collectively engaging with something meaningful, so why not Judaism at the local synagogue?

“People want something in their lives that means something,” Fradkin said, and they build their lives around what they feel matters. While acknowledging the musical means of connection might not be for everyone, Fradkin ended on the note that the goal is to inspire Jews to live more spiritual lives while strengthening an active connection to Judaism.

Powered by Froala Editor