Deuteronomy 6:4

Hear, O Israel, the L-rd is our G‑d, the L-rd is One.

This is the phrase that, for three and a half millennia, has bound together the Jewish people. The words have danced through our throats in joy, dripped from our tongues in sorrow, slipped from our mouths in relief. They have evolved into the backbone of our spiritual DNA.

The Torah commands us to say Shema thrice daily: once as we gird our loins against the day’s challenges, once in the afternoon to fortify ourselves, and once as we ready ourselves for sleep. In the past year, I have attempted to integrate this prayer into my routine. Though I do not have the discipline to say it every morning, afternoon, and night, I have tried my best to whisper this prayer in the darkness as I settle into bed and squeeze my eyes shut in preparation for sleep.

Infancy 6:1

In kindergarten, my teacher told us that saying the Shema every night before bed was a way to protect ourselves against nightmares. We were gathered in a circle, knees jutting against each other, elbows and hands awkwardly spread out on the blue carpet adorned with depictions of the seven days of creation. She stood above us and explained that if we held our hands to our eyes and whispered G-d’s words as we pulled quilts to our shoulders, clutched stuffed animals or blankets to our chest, and waited for sleep, he would protect us. He would take the swirling evils of our subconscious in his fist and crush them into dust.

Infancy 8:1

When I was eight, I had my first nightmare. I was trapped somewhere; a family friend’s grandmother was turning everyone green, and there were grocery store carts that looked like cars. The next morning, I woke up shining with sweat and fear.

I lay in the bed that hours ago I had been ecstatic to occupy. We were on Cape Cod, and the bedroom I shared with my friend was something out of a fairytale cottage. Rays of autumn light streamed through a window, dividing it in half. My friend’s bed sat safely nestled against a wall on one side of the glass. Mine was tucked against the other. The white frills of the pillow and duvet made the beds look like heavenly clouds. The divide between heaven and earth wasn’t the ocean just down the road. Rather, it was here, just underneath me. The space between mattress and hardwood floor marked the difference between celestial and mundane.

Deuteronomy 6:7

You shall teach them thoroughly to your children, and you shall speak of them when you sit in your house and when you walk on the road when you lie down, and when you rise.

Perseverance 1:1

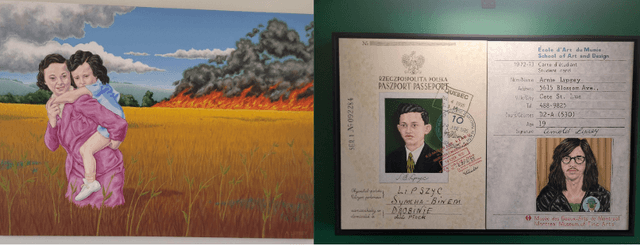

Our formal Holocaust education began in third grade, and once again, our teachers lectured us on the Shema. They told us how during the war, mothers, forced to choose between their children’s lives and their religion, handed their toddlers off to Christian orphanages. As they stroked their children’s hair and hugged them for the last time, they whispered the Shema in their ears and told their children never to forget the prayer, to whisper the words to themselves silently every night. The words would nestle in their growing bones, develop alongside cartilage and flesh, and fortify their bodies against the hardships of the world.

]Many of these children would never see their mothers again.

Adolescence 14:1

In eighth grade, we were told to write a paper about our theological beliefs. I was sitting in class, scrolling through Redbubble, looking for funny laptop stickers as only a fourteen-year-old does. It was my last class of the day, and I was itching to go home. My feet were swinging back and forth, absentmindedly bouncing off the metal of my chair. In every sense of the phrase, I was completely and utterly zoned out. But, as my teacher introduced our assignment and gave us our theological options—agnosticism, theism, or atheism— and told us to decide, something inside of me awoke. My mind began to churn and spark. Never before in my life had anyone asked what I believed; never had the inner workings of my own mind been connected to the beliefs I held in my soul.

My parents assumed I would believe the same things they did—G-d existed, community existed, and conservative traditions bound both together. They figured I would practice the same way; Shabbat would remain a Friday night family dinner full of chicken, discussion, and two minutes of prayer, followed by everyone running off to their rooms to watch TV or do homework. My first Jewish Day School taught me as if I was an orthodox Jew and held every value that they did—G-d was lofty, mighty, and unreachable. Slogging through daily prayer, covering my shoulders, studying Torah—those were the steps I could climb so I could at last whisper into G-d's merciful ear.

Faced with my first actual religious decision, teenage spitef took over. I considered the world I lived in—a world I hated for its imperfections, its brokenness, its mess. A world I had often felt estranged from, a chasm created between myself and matter by all the pain and strife of adolescent struggle. No perfect being would design a world cracked at the core, seeped with the poison of a harrowing reality. A world like this could not have possibly been created by a G-d. So, I ran with all my might away from the word and its alleged creator. I declared myself an atheist.

Infancy 8:2

I lay in bed floating above the Earth, mind and body still reeling from the revelation that sleep would not always be peaceful, that things would not always be perfect. As I untangled myself from the sheets I had knotted myself in that night, I realized that the only way to protect myself from nightmares, the only way to preserve sleep as my haven from the mess of the world, was to follow the instruction of my kindergarten teacher. I would say the Shema every night. The words would steel my neurons against the terrifying unrealities of my own subconscious.

You shall love the L-rd your G-d with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might.

Perseverance 1:2

When the Holocaust ended, the DNA of the Jewish community lay unwound and tangled under the feet of hatred, oppression, and death. Six million were murdered, hundreds of thousands were refugees, and shards of families shattered by hatred were scattered across Europe. Many Jewish children who had been taken in by strangers remained separated from their people. Picking up the pieces, stitching up the wounds, reforming the characteristics of a community broken and traumatized was going to be agonizing and slow. As a start to this long process, Rabbis from the Orthodox Union began to search for Jewish children hidden by their mothers in orphanages and monasteries.

These former safe havens did not want to give up these children, though; they clung onto them and claimed them as their own. Employees would inform Rabbis that there were no Jewish children in their establishment, and in the rare case their existence was admitted, the Rabbis would not be allowed to see them.

Adolescence 14:2

Once I had labeled myself an atheist and resigned myself to the fact that I was a nonbeliever, something changed within me. G-d became a far-fetched entity; nightmares became no worse than reality, and faith’s candle dripped scorching wax on my hand until it burned out.

Once that happened, “Jewish” became a description, not a doctrine. I went to Jewish School. I celebrated Jewish Holidays. I was a Jew by label, by community, but not necessarily by faith. I forgot the words of Shema. I was no longer able to repeat them by heart. They slipped out of my brain and struggled to rise from my throat.

Perseverance 1:3

Despite the challenges, Rabbi Eliezer Silver insisted on seeing the children,, arguing with the nuns late into the night until he was finally granted access. The youths had already tucked themselves into bed, wrapped themselves in their blankets, and prepared themselves for sleep. But, Rabbi Silver still wove between the beds, chanting, “Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai Echad.” These words echoed through the room and reverberated through the ears of the Jewish children.

As their mothers’ last words sprang from Rabbi Silver’s mouth, something awoke in these children. Some instinctively clapped their right hand over the eyes as they whispered the final words of the Rabbi’s sentence. Others’ voices rose in twists of anguish and prayer as they called for their lost families, their lost mothers, their lost identities, their lost people.

Adolescence 17:1

After years of resting on a pedestal of indifference and disdain, in eleventh grade, something within me changed. In 2021, I emerged from a year of sitting on my bedroom floor, isolated and confused. I broke free of COVID’s devastating realities and the time when communities were unable to reunite face to face. I yearned for a connection beyond a screen and beyond physical touch. I yearned for a community built on a foundation of shared values, hopes, practices, and traditions. I yearned to find a middle ground between the gullible infant and the sullen, barbed adolescent.

And with that, Judaism became more than another thing I tolerated as part of my routine; it became a guiding principle. I peered behind the curtains of my morality, dissected its essence, and found the word of the Torah encoded into it, the graceful curves of the Hebrew alphabet seamlessly intertwining with my values and beliefs. I tried to refrain from work on Saturdays and holidays and attempted to find the meanings in the prayers I had so often found myself mindlessly skimming over. During my gap year, I began to try and say the Shema again.

This rediscovery was not a concrete moment. It was no strong, resounding statement filled with tears and instant clarity. It was not a moment of realizing nightmares could be prevented by prayer, that one possesses the power to decide their own beliefs, or that a mother’s last words were the key to a community’s continuation.

It was slow and painful, marked by the growing pains and mistakes of young adulthood and change. Faith’s waning flame was not instantly revived within me. Yet I believe that all along, as my mind stretched and grew, as my bones shifted and expanded, as my identity morphed and changed—the Shema remained nestled within me.

Powered by Froala Editor