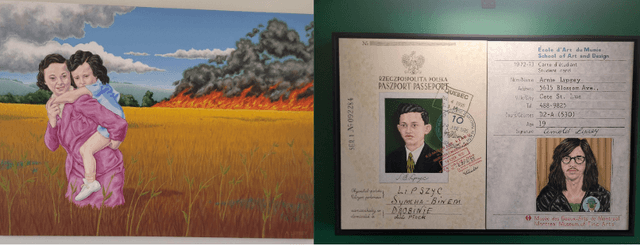

“Shtetl in the Sun” is the newest temporary exhibit at the Museum of Jewish Montreal (MJM). It showcases photographs taken from 1977-1980 by Miami Beach native Andy Sweet, accompanied by the contemporary touch of kitsch ceramic pieces made by Toronto-based artist Jonah Strub.

The exhibit’s title is oxymoronic. Upon hearing shtetl—meaning ‘town’ in Yiddish—I imagine a cold, Eastern European landscape with Jews bundled in thick coats and big hats. The sandals and sundresses worn in Sweet’s scenes seem antithetical to this pre-Holocaust Ashkenazic existence. His sun-filled images encapsulate Miami Beach’s culturally thriving Jewish community, which was burgeoning post-WWII, and persists today as many North-American Jewish families maintain strong connections to Florida’s southern coast.

While exploring the exhibition space, you can almost hear kvetching from Strub’s small sculptures of Jewish-Floridian women—a dynamic that immerses you in a poolside vibe among Miami Beach’s late ‘70s Jewish crowd.

Tucked away on a bench at the exhibit’s opening night, I spoke with Alyssa Stokvis-Hauer, the exhibit’s Artistic Director. She explained that the swagger and flamboyance of Sweet’s subjects is a signature style called Camp.

Stokvis-Hauer described Camp as “a sensibility sort of adjacent to kitsch. It's big, it's brassy, it's bold, it's unapologetic, it revels in vibrancy.” Surrounded by Sweet's photographs, she pointed out how his subjects embody Camp with bright pinks, leopard print, and matching purple bathing suits. Adjacent to this flashy fashionability, one photograph shows a Hasid in his dark suit walking briskly across the beach; in another, a second suited Hasid stretches his arms from a tree branch.

The vibrant Camp theme pervades the exhibit. Camp became an emblematic look in Western pop-culture, embraced by iconic Jewish women like Barbara Streisand and Amy Winehouse, Stokvis-Hauer noted. She explained that “[Camp] has continued today in a major way, especially within the Queer community.” While the big-wig, unapologetic approach is integral to Drag performance, it is also prevalent in mainstream entertainment, with artists like Beyonce and Lady Gaga emboldened by its energy.

For Stokvis-Hauer, “[Camp] signifies an element of pride and ‘I’m here.’” As many of Sweet’s subjects were Holocaust survivors, to champion this highly expressive existence is particularly powerful. Their blossoming response of colour is a striking contrast to the bleak iniquity they endured mere decades prior. Stokvis-Hauer also noted that this loud self-assertiveness in Camp, as it is embraced by the Queer community today, is an example of interconnectedness between Queer and Jewish identites—a phenomenon further illustrated by McGill professor Darren Rosenblum in their profile piece with Nu.

Combining the respective sensibilities of Sweet and Strub was in part inspired by Judaism. Stokvis-Hauer expressed that “there is a lot of dialogue and discursiveness built into the Jewish faith.” She raised that a similar encouragement of discussion is also inherent in art “because there are so many different interpretations or ways of connecting with one art piece.” This quintessential Jewish practice of bringing perspectives together is manifested in the exhibit. As the perspectives of Sweet and Strub come into dialogue with one another, the melding of their art forms creates a third entity which allows the exhibit visitor to experience an even more enriched sense of the ‘70s Miami Beach scene.

You may have heard the saying two Jews, three opinions. Stokvis-Hauer spontaneously adapted this saying into “one art piece, three opinions” – suggesting a plurality of potential points of connection visitors can have to the exhibit.

Elucidating another subtle Jewish theme, Stokvis-Hauer mentioned Mah Nishtana, a Passover tradition wherein the youngest person at a Seder must answer four questions concerning the holiday’s practices. Both this tradition and the exhibit exemplify intergenerational inquisitiveness within Jewish culture. Just as the younger generation is encouraged to engage with Judaism during Passover—while generations apart, Sweet and Strub both endeavor to capture a particular essence of Jewish culture in their art.

My experience at Shtetl in the Sun served as a reminder of the Jewish people’s resilience and vigorous tradition as it flows into artistic expression. Stokvis-Hauer underscored that the bold aesthetic captured by Sweet imparts a clear message: “here we are, we're not going anywhere” – a message still embraced by many today. After appreciating this moment of vitality that brought joy to Jewish life following WWII, I was imbued with a renewed sense of pride in my heritage. This exhibit is definitely worth a visit—it might even inspire you to add a bit more colour to your wardrobe.

Powered by Froala Editor