Last week, on February 2nd, Jewish people across the globe celebrated the festival of Tu Bishvat, often described as the “birthday of the trees” or a kind of Jewish Earth Day. It is meant to mark the end of the depths of winter, symbolizing renewal and new beginnings. Though the festival does not appear in the Torah, it is a holiday rich in history and tradition.

Much like Hanukkah, Tu Bishvat emerged as a post-biblical festival, with origins tracing back to its use as a practical tool for farmers in ancient Israel. The festival is first mentioned in the Mishnah, which commands farmers not to eat any of a tree’s fruits until it is three years old. This emphasis on age makes the tracking of trees “birthdays” important.

The timekeeping aspect of Tu Bishvat also served a purpose for tithing: the religious practice of giving one tenth of something to God and charity, creating an obligation for farmers to bring one tenth of their fruits (a tithe) to the Temple of Jerusalem each year. Farmers could not use fruits from a previous year for tithing, making Tu Bishvat essential for keeping track of what year the trees bore their fruit.

In the Middle Ages, Tu Bishvat traditions were established. Kabbalists, believers in Jewish mysticism, began holding Tu Bishvat seders, much like the traditional seder held on Passover. The Tu Bishvat seder customarily included foods like barley, figs, grapes, pomegranates, dates, olives, wheat, and barley—all described as fruits of the Holy Land in the Torah.

Communities throughout the diaspora have found their own meanings in the festival. In the Bene Israel community of India, legend has it that Jews first arrived in the country on the 15th of Shvat, the day of Tu Bishvat. Around 1700 years ago, a group of Jewish men and women coming from Israel were shipwrecked off of the Konkan Coast before being saved by Elijah the Prophet. Now, annually on Tu Bishvat this community gives thanks and honours this story in a ceremony called Malida, consisting of a series of prayers to Elijah Hanavi and other ancestors.

However, this tradition is not necessarily exclusive to Tu Bishvat. Rabbi Romiel Daniel of New York explains that Indian Jews partake in Malida on any auspicious occasion, including the anniversary of their ancestors’ arrival in the region. Though it is practiced on other occasions, Malida is just one example of the diversity of Judaism seen through the celebration of this agricultural new year.

Like many Jewish holidays, the history of Tu Bishvat also represents resilience and hope. In 1943 a group of Jewish children, alongside a woman named Irma Lauscher, planted a tree to celebrate Tu Bishvat while in detention at Theresienstadt. They are said to have declared “As the branches of this tree, so the branches of our people!” In planting a tree, a universal symbol of life, these children resisted the daily oppression and violence of life in a concentration camp.

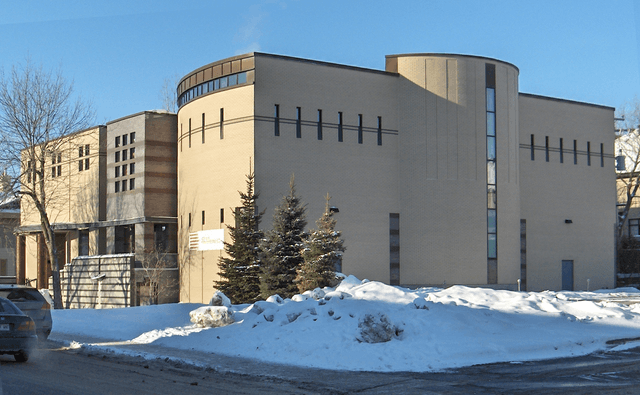

Tu Bishvat in Montreal in 2026 may look a little different than it does for the ancient Israelite farmers, Kabbalists in the Middle Ages, or the Jews of India. Though it may feel like Montreal’s leafless trees and piles of snow prevent the festival from being celebrated as it ought to be, there is still much meaning to be found in this celebration of trees. The “birthday of the trees” in this modern context can be taken as an opportunity to reflect on the importance of nature in Jewish history and to form new, unique traditions.

Powered by Froala Editor