Timothée Chalamet’s Marty Mauser, a competitive table tennis player, commands attention like a king holding court. Unlike a king, however, Marty has no sense of propriety. When interviewed by a mob of journalists about an upcoming match against Holocaust survivor Béla Kletzki (Géza Röhrig) at the British Open, Marty declares, abrasively, “I'm gonna do to him what Auschwitz couldn't.” Met with horrified looks, Marty adds in defense, “I’m Jewish, so I can say that.” Marty’s Jewish identity remains an integral part of the movie and his character.

Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme follows its titular character’s obsessive pursuit of the world table tennis championship. Hailing from Manhattan’s Lower East Side, a myriad of obstacles stand in the way of victory: a job he hates at his uncle’s shoe store; a hypochondriac and manipulative mother; and a girlfriend Rachel (Odessa A’Zion), who is married to another man but pregnant with Marty’s child.

As pedantic as he is driven, Marty bristles when table tennis is referred to as “ping pong.” Unlike other public figures in the 1950s, he doesn’t Anglicize his Jewish last name, Mauser, to something more palatable. Instead, he demands to be called Marty Supreme. At the British Open, horrified by having to share a hotel room, he schemes his way into a suite at the Ritz. Marty believes he deserves nothing but the best.

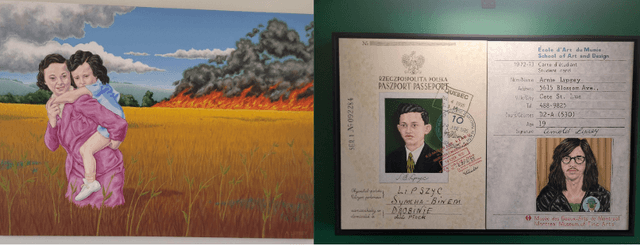

Marty’s ego is contrasted with the selflessness of Béla Kletzki, Marty’s opponent and friend. A survivor of the Holocaust, Kletzki’s successful table tennis career gave him a reputation of being good with his hands. Aware of this, the Nazis assigned him to defuse bombs around the camp’s perimeter. On one occasion, Kletzki discovered a beehive in the woods, smeared honey on his chest and back, and allowed the men in his barracks to lick it off him for sustenance.

In one of the film’s most controversial scenes, Marty’s main antagonist, business man Milton Rockwell, sneers at Kletzki that his son “died liberating you people” upon learning he survived Auschwitz. Marty interjects—it was the Soviets who liberated Auschwitz, not the Americans—and urges Kletzki to recount this story of survival. It is the only flashback in the movie. The sequence’s surrealist quality punctuates the gritty realism of the rest of the film. The background of the shot is completely black, with light only trained on Kletztki and the starving inmates who surround him, reminiscent of a Baroque style painting.

Given the chaotic humour in the rest of the film, it is unclear if Kletzki’s story about the honey is meant to be darkly comedic or deeply tragic. Journalist Fran Hoepfner described a “smattering of uneasy laughter” in her article in Vulture, while the Jewish mother of my friend called the sequence just plain “stupid.” I side with Hoepfner: the scene is essential.

Marty’s self-centeredness exposes a generational divide between Holocaust survivors and their American-born counterparts. Marty frames his ambition as historical revenge, proclaiming himself “Hitler’s worst nightmare.” His quest stretches beyond the Holocaust; at one point in the film, Marty steals a piece of the pyramids for his mother, declaring “We built this.” For Marty, success is proof of survival.

But Kletzki, who has gone through unimaginable suffering, feels no need to be the best. When the pair accept work as a ping-pong act opening for the Harlem Globetrotters after the British Open, Marty is humiliated, while Kletzki seems content just with the opportunity. It’s enough for him. Perhaps because Marty has not experienced the same hardships that Kletzki has, he feels far more compelled to achieve a symbolic Jewish victory. Kletzki suggests an alternative: true victory over Hitler does not lie in dominance, but in surviving, caring for others, and living a full life.

In the end, Marty leaves the championship defeated and returns to New York. At the hospital, peering through the nursery window and seeing his newborn son for the first time, he bursts into tears. The world is unforgiving and ruthless; all-encompassing, lifelong ambitions like Marty’s can be easily crushed. Yet, gazing upon his son, Marty may finally realize what Kletzki already knew: after years of war and destruction brought on by Hitler, caring for someone else — even if it offers no promise of glory—is itself a form of victory.

Powered by Froala Editor