Holocaust Remembrance Day always arrives quietly for me. There is no fixed ritual that marks it, no ceremony I attend each year. Instead, it settles into the day as a presence I have learned to live with. I think about the relatives I never met, whose names survive only in fragments, and about those who lived long enough to rebuild lives that made my own possible. I think of my great-grandmother, Chana, who was imprisoned in Birkenau and survived. Her survival is not a story I can fully understand. It is something I inherit. This year, on the evening of January 27th, I walked through McGill’s campus to attend a lecture marking the day. It felt important to place private remembrance alongside shared reflection.

Professor Aliza Luft’s talk, titled “Between God and Vichy: Religion, Race, and the Holocaust in France,” did not offer comfort. Instead, it asked the audience to examine how authority, trust, and moral influence shaped a moment of crisis. Luft, an assistant professor of sociology at UCLA and a Montreal native, began by noting the familiarity of the room. She recognized faces from her childhood, including her fourth grade Hebrew school teacher and the mother of a close friend. The moment grounded the lecture in return rather than distance. This was scholarship shaped by lived connection as much as archival research.

At the center of Luft’s work is the Catholic Church in France and its influence over how Jews were understood during the Nazi occupation. The Church was not simply silent or inactive, but deeply involved in shaping perception through its authority, language, and private assurances. Catholic leaders often conveyed sympathy for Jewish population of France behind closed doors while avoiding public confrontation. These mixed signals shaped how Jews interpreted danger and how Jewish leaders planned for survival. Luft emphasized that decisions during the Holocaust were rarely made with clarity or certainty. Instead, they unfolded through quiet negotiations and personal relationships.

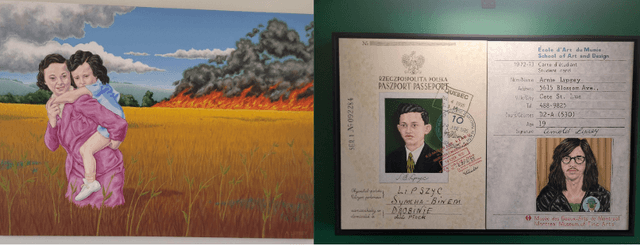

Jewish leaders, facing mounting threats, often trusted institutions that had long promised protection. That trust was not irrational; it was reinforced by religious and political authorities who suggested that restraint and patience would be rewarded. One image Luft described remained with me long after the lecture ended. She spoke of a man in a French concentration camp wearing his French army medals beside the yellow star sewn onto his clothing. The image captured the painful tension between loyalty and abandonment. It reflected how identity, affirmed by institutions for generations, could suddenly offer no protection at all.

Two days later, I spoke with Luft in a follow-up interview. She reflected on her family’s immigration to Montreal after the Holocaust, leading to her upbringing in Hampstead. She also discussed her broader research interests, including her work in Rwanda on behavioral variation. Her focus is on understanding how individuals and institutions that make choices under extreme pressure and/or violence, including why some act publicly while others remain “privately sympathetic.”

Sitting in the audience on Holocaust Remembrance Day, I was struck by how listening can itself be an act of remembrance. Luft’s lecture did not merely recount what happened, but asked how people understood their world as it was unraveling. It reminded me that remembrance is not only about honoring loss. Remembrance is also about examining how power shapes belief, how trust can be encouraged and misused, and how the failure of institutions can determine the fate of entire communities.

Powered by Froala Editor