On the evening of January 16th, 2026, Nu attended the release show of Boston-based trombonist Michael Prentky’s newest album, sad boy:ADD:apocalypse. The performance, which took place at La Sotterenea in the Plateau, featured an energetic opening set by Montreal-based Klezmer band, Kallisto, live readings of Prentky's original poetry, and traditional Yiddish line-dancing.

Throughout the show, Prentky simultaneously filled the roles of conductor, poetic-vocalist, and trombonist. Prentky’s original and rather eclectic compositions were performed alongside his band, which consisted of four trombones, two guitars, two violins, a cello, a tuba, and drums. Before the performance, Prentky led a tutorial of a traditional Yiddish line-dance, the Terkisher, encouraging audience members to dance once the music began. After several minutes of fun, yet highly disorganized Yiddish dancing, the band adopted a more rock-adjacent sound. Nevertheless, a distinct hint of Klezmer influence remained throughout the performance, maintained by the prominence of Prentky’s horn section and by Prentky’s Niggun-style humming that dominated many of the interludes between songs.

Many of the attendants were already well-acquainted with Prentky, as well as Yiddish song and dance, through the organization KlezKanada. KlezKanada, which hosts a week-long retreat for Yiddish enthusiasts in the Laurentians every summer, was praised by Prentky as a community to which he feels a deep sense of love and connection. In an interview with Nu before the show, Prentky shared that he openly mourns the destruction of Jewish Shtetl life in Europe. As such, he considers the KlezKanada retreat to be the most authentic creation of an immersive Yiddish environment that we can hope to form as modern individuals in North America.

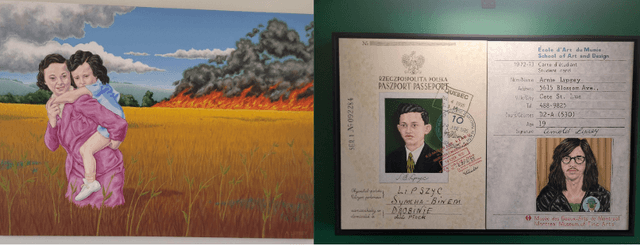

Prentky’s passion for Klezmer is rooted in his love of Yiddishkeit. For Prentky, Yiddishkeit is not simply a synonym for ‘Judaism.’ Rather, it is the celebration of the Jewish cultures that emerged in Eastern Europe, and which were, tragically, largely destroyed during the Holocaust. As such, Prentky’s celebration of Yiddishkeit is a conscious effort to reclaim a connection to an ancestral culture that was taken from him—and from so many others—as a result of the Holocaust and its enduring impact on all facets of Jewish existence. However, the question remains in Prentky’s mind: How much of this culture can we actually bring back?

Although we may not be able to reinhabit the physical spaces in which many of our ancestors lived for centuries in Europe, we maintain the power to celebrate their legacy through cultural observances. Indeed, Prentky’s show was a great example of such celebration. One moment especially struck me with a sense of hope in our ability to succeed in such an undertaking.

Toward the beginning of the show, an attendant named Josh took it upon himself to teach the rest of the audience how to dance the Zhok, which is often defined as a slow Hora. In this moment, gathered hand-in-hand and moving in unison with a dozen other Jews and fellow Yiddish-lovers, I felt a potent wave of love, connection, and community gently wash over me. I was dancing the dance of my ancestors, physically honouring their legacy with the movements of my body.

If Prentky’s performance taught me anything, it is that Yiddishkeit is alive and well. However, in the same way that the celebration of Yiddishkeit has the power to foster joyous and vibrant community, its continued existence relies on Jews today to make intentional efforts to embody, uphold, and share its traditions.

Powered by Froala Editor