Upon returning to Montréal in early January, my friends and I exchanged stories from our winter breaks, with Christmas being a highlight for many of my non-Jewish friends. They told me about their cherished family traditions: attending meaningful church services, decorating their homes, and watching festive movies. Wanting to include me in their conversations, they asked me if my traditional Jewish family did anything special on Christmas. Many were surprised to learn that I participated in Christmas festivities by eating wonton soup (chicken, not pork) and lo mein noodles at my favourite local Chinese restaurant. What surprised them further is that this is not a quirky family tradition, but a cultural practice that has endured among North American Jewry for nearly a century.

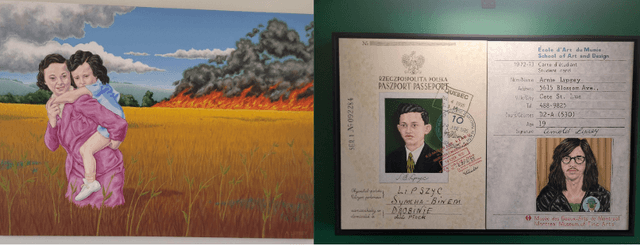

For centuries, Eastern European Jews marked Christmas Eve and Christmas Day by remaining at home and playing card games. Pogroms often occurred on Christmas, and Jews were barred from appearing in public in some places, with the holiday being referred to as Moyredike Nahcht (Fearful Night) in Ukraine and Galicia.

The Jewish fascination with Chinese food dates back to the late 19th century. The Lower East Side of Manhattan was home to large Jewish and Chinese communities, which comprised the two largest non-Christian immigrant groups in the United States at the time. The first mention of Jews eating at Chinese restaurants appeared in 1899 in the weekly journal The American Hebrew, which criticized Jews for eating at non-kosher establishments, particularly Chinese restaurants. However, Chinese cuisine soon became accepted and popular among Jewish immigrants.The New York Times reported in 1935 that Eng Shee Chuck, a Chinese restaurant owner, brought chow mein and toys to a Jewish orphanage in New Jersey on Christmas.

While many Eastern European Jewish immigrants were insecure about their social standing in America, they often found comfort and acceptance in Chinese restaurants, as Chinese immigrants were likewise regarded as non-Westernized outsiders. Indeed, a 1922 Yiddish advertisement for Tangerine Gardens in Forverts promised Jews that they would “feel at home” at their restaurant. Jews, who viewed Chinese food as cosmopolitan and sophisticated, also felt welcome in Chinese establishments because they lacked the Christian iconography that typically decorated the walls of other restaurants, particularly Italian ones.

Christmas brought a feeling of alienation for the American Jewish community; Chinese restaurants, which were open on Christmas, became a haven for Jews. Jews gathered with their family and friends at Chinese restaurants instead of staying home, and the holiday transformed from a day marked by fear into a day where Jews developed cultural traditions and a distinct Jewish American identity. As Jewish communities spread throughout North America, the tradition endured. Eating Chinese food on Christmas remains a prominent North American Jewish tradition, with Chinese restaurants in Jewish neighbourhoods taking reservations for Christmas Day well in advance.

Zach Muraven, a Canadian Jewish student who eats Chinese food on Christmas each year, told Nu that “Jews eating Chinese food on Christmas feels like the perfect comedic pairing” because the combination of two “distant cultures, on a day which belongs to neither of them, became an inter-generational tradition.” “How could you not eat Chinese food on Christmas?” he joked. Liam Popper, another Canadian Jewish student, describes eating kosher Chinese food on Christmas as “a rite of passage.”

For many Jews, eating Chinese food on Christmas is not just delicious, but a meaningful reminder of Jewish history and the formation of North American Jewish identity.

Powered by Froala Editor